The Optus Data Breach incident has shed some much-needed light on the need for robust, top-down board governance over organisational data and information. It is evident that this attack has demonstrated the need for organisations to sufficiently invest in cyber-attack prevention, detection and response. While the Optus data breach is still under investigation, the consensus from government statements and external experts seems to be that that human error played a significant part in this data breach. It is not uncommon for human factors to either cause or amplify technical weaknesses resulting in a data breach, about one-third of all reported personal data breaches from OAIC’s Notifiable Data Breaches Reports are attributed to human error as the primary factor.

Whether data breaches are caused by human error or technical fault, security experts widely agreed that organisations should consider data breaches a question of ‘when’ rather than ‘if’. This in turn means that senior executives and board members should ensure they have a good grasp of the ‘what’ and ‘where’ of data within their organisation. These are important factors not only for general information governance, but key elements for implementing an effective data collection, use and disposal lifecycle which is crucial for mitigating the impact of future data breaches.

The causes of over-retention

Most organisations – businesses and government agencies alike – are collecting and generating exponentially increasing volumes of data each year. Fewer organisations are successfully disposing of data that is no longer needed for regulatory retention requirements or for business purposes, as required under Australian Privacy Principle 11.3. This may be due to a desire to retain data for commercial purposes, misunderstanding of regulatory requirements, low costs of data storage, difficulties in implementing data disposal policies in complex technical environments or a combination of all these factors.

Optus has indicated it was keeping identity information obtained from new customers for up to six years as per the requirements of the Telecommunications Consumer Protections Code. However much of the significant personal information apparently lost in this breach, such as passport, licence or Medicare details, would not seem to be required for compliance with this Code. It would appear that a telecommunication provider would only need to retain this level of information to meet requirements under the Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act 1979 which requires them to retain specific communication metadata and customer identification information for two years.

As the Attorney- General, Mark Dreyfus said, “They don’t seem to me to have a valid reason for saying we need to keep that for the next decade.” The challenge for governments and regulators is to ensure that regulations clearly set out the retention periods for specific categories of data, along with sufficient penalties for compliance failure. As it stands it is common for organisations to have a default retention period of 6 or 7 years for all categories of documents, and it is also less common for organisations to have implemented robust data retention lifecycle regimes which ensure that data and information is permanently deleted when it is no longer required.

The risks of over-retention

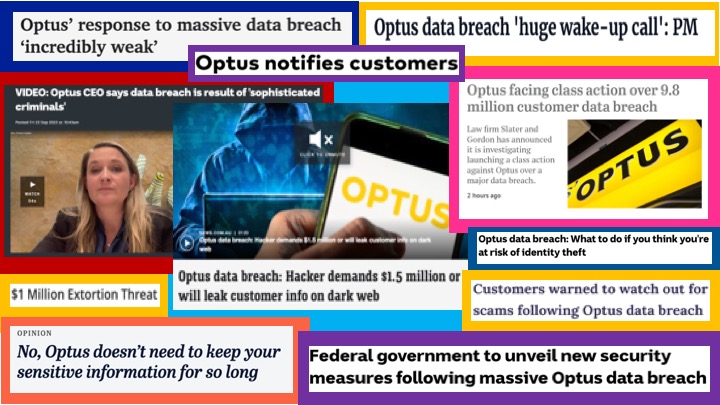

Until an organisation has faced a significant data breach it is difficult to comprehend the resources needed to respond, contain and remediate a significant data breach, along with the stress and costs involved in responding to stakeholders, media and regulators. The extensive media coverage of the Optus data breach and associated reputational damage, provides an opportunity for boards and senior executives to consider how effectively data and information is, or perhaps is not, governed within their organisations.

While the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) set the global benchmark for privacy regulations in 2016, the long awaited overhaul of Australia’s Privacy Act is still pending. The updated Privacy Act is likely to substantially increase fines meaning Australian organisations will have an increased regulatory incentive to improve personal information lifecycle management and training of staff to protect personal information.

Failure to properly govern and protect information assets and implement a robust data lifecycle management program poses significant risks for all organisations.

How organisations can respond

Rather than focusing solely on cybersecurity, a more holistic top-down governance model is needed to manage data as part of the information assets across the enterprise. This coordinated approach is both more effective in managing risks and enables organisations to maximise the value of data and information in accordance with the organisation’s overarching strategic objectives.

A key challenge facing boards and senior executives is ensuring their organisation understands where sensitive data and information resides and that it is adequately secured and protected including appropriate classification, controls around use, re-use and storage, and permanent disposal of data in accordance with regulatory requirements. While responsibility for these activities have often been separated into differing organisation silos, effective information governance requires that each aspect is coordinated and aligned holistically across the organisation.

To achieve this aim, organisations should be allocating sufficient budget investment into internal governance of data and information activities including: alignment of internal policies and procedures to adequately secure and protect data; continual training and upskilling of staff; and internal auditing to ensure the policies and procedures are being adhered to along with identification and remediation of gaps.

Author

Susan Bennett, LLM(Hons), MBA, CIPP/E, FGIA, GAICD

Founder and Executive Director InfoGovANZ