Information is critical to decision-making and plays an essential role across all three pillars of governance.

Information is critical to decision-making and plays an essential role across all three pillars of governance.- The emerging driver of good information governance globally is compliance with regulatory obligations, particularly with the growth in global privacy laws.

- Effective information governance requires top-down board and senior executive leadership.

Good corporate governance in the data driven and digital economy poses significant challenges for Boards and seniors executives. This article highlights the importance of information governance to ensure there is a unified strategy and framework to govern information effectively. Good information governance enables organisations to maximise the value of information as a business asset while minimising risks and costs, particularly those associated with data breach.

Over the last 25 years there has a lot been written about corporate governance. There have been debates about the value it adds to an organisation and even the share price on the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX). One fact that is not disputed is that the companies and organisations still fail, in a corporate governance sense. This has been illustrated through the media in September 2018, with the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) public dismissal of its managing director and then the forced resignation of the chair of the board, a few days later. Similarly, the scathing criticisms of the four major banks and other financial services providers through the Interim Report[1]of the Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry (Hayne royal commission) in respect of their culture and corporate governance.

Previously, it has been noted, that there is a “three pillar”[2]approach to good corporate governance and sometimes, both management and boards, get a little confused as to the distinction between the specific pillars of corporate governance, due diligence and compliance. Before briefly explaining the importance of each of the three pillars of governance, it is essential to note that the role of technology in every organisation has changed how and why things are done and recorded. It is critically important that the board and by entension the whole organisation, understand information governance is key to good corporate governance. Unfortunately, research by the Information Governance ANZ[3]shows that there is confusion as to what this concept means and who should be responsible for it.

It is possible to express information governance as a component or one aspect of corporate governance, but this misses the point, that information is critical to decision-making and plays an essential role across all three pillars of governance from corporate governance to due diligence to compliance. The importance of technology was explained in the 2018 directors’ top concerns, under the title #SEMTEX.[4]This will be explained in more detail below.

Corporate governance

The amorphous nature of corporate governance is what makes it simultaneously defies definition, but many commentators have attempted to definitively account for corporate governance.

In 1992, the now world famous Cadbury Report took a simple approach, proposing that corporate governance is ‘the system by which companies are directed and controlled’. In Australia, the ASX Corporate Governance Council’s Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations, third edition adopted the following definition,

‘The phrase “corporate governance” describes “the framework of rules, relationships, systems and processes within and by which authority is exercised and controlled within corporations. It encompasses the mechanisms by which companies, and those in control, are held to account.” Good corporate governance promotes investor confidence, which is crucial to the ability of entities listed on the ASX to compete for capital.’

The fourth edition is currently under consultation and flagged to publish in 2019.

Our preferred academic definition is found in Cochran and Wartick’s 1988 publication Corporate Governance: A Review of the Literature, which suggest that corporate governance is “an umbrella term that includes specific issues arising from interactions amount senior management, shareholders, boards of directors and other corporate stakeholders”. There are numerous studies[5]as to the benefits of corporate governance for global entities, whether they be the transnational corporations or the more traditional multinational companies. Around the globe, by far the majority of business entities are privately owned, with a small percentage being quoted on a local stock exchange, in a single legal jurisdiction.

Corporate governance has many elements, including risk management, due diligence and compliance. They are not terms of art, but certainly three distinct, yet inextricably fused elements of corporate governance. With an overlay of information governance, it is easy to see how confusion can arise.

Internal Due diligence

Due diligence, in the corporate governance context has evolved beyond its original role as a defence for transactions (buying and selling businesses or fundraising prospectuses). Due diligence is now seen as within a corporation’s internal operations that the link governance (at the board level) to the operational compliance programs. The use of the expression ‘due diligence’ to describe the system implemented within a corporation of checking day-to-day legal statutory compliance. These risks and duties can cover a range of issues, but often are linked to legal risks, such as consumer laws, property rights, (including physical and intellectual property), employment relations, environmental, corporate and privacy law). Due diligence and compliance are related but not to be treated as one and the same.

A simplified internal due diligence risk model, would normally have six steps, commencing with a legal risk audit. This is followed by a compliance plan for the whole entity or particular operating divisions. The next step normally involves the implementation of the compliance plan and at some stage (set time period) a review of the established compliance program. It is important that the compliance programs, through the due diligence process are formally reported to the board of directors. Finally, after a couple of years, any due diligence and compliance system should be re-evaluated and another audit of risk be commenced.

Compliance programs

All commercial environment have become increasingly regulated in recent years. The 2018 Hayne royal commission is illustrating that even Australia’s largest corporations are failing to have good governance and compliance systems, which have led to misconduct in the financial services sector. Compliance is demanded with a greater number of statutes, regulations, industry standards and principles than ever before. What is more, society is becoming more litigious, and regulators are having their arsenal bolstered by greater powers and a greater range of penalties. Although, there has been criticism of the lack of enforcement by ASIC and APRA, many other regulators regularly enforce their, criminal, civil and civil- penalty provisions. Out of the Hayne royal commission, it is reasonable to assume that ASIC and APRA will be conducting much more enforcements of the law than in the previous decade. It can be presumed that shareholder class actions will continue where there have been corporate governance failures and breaches of the law.

Information governance

What has become apparent over the last decade is the importance of information relating to the organisation. There are many different priorities, but the impact of e-discovery in litigation and the traditional requirements of archiving records for future management, together with increasing numbers of data breach have led to an explosion of laws and compliance issues. The EU impact of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the introduction of the Notifiable Data Breach Scheme (NDB Scheme) in Australia this year, are two examples of how boards have a much greater responsibility to have a systematic approach to information governance.

What is Information Governance

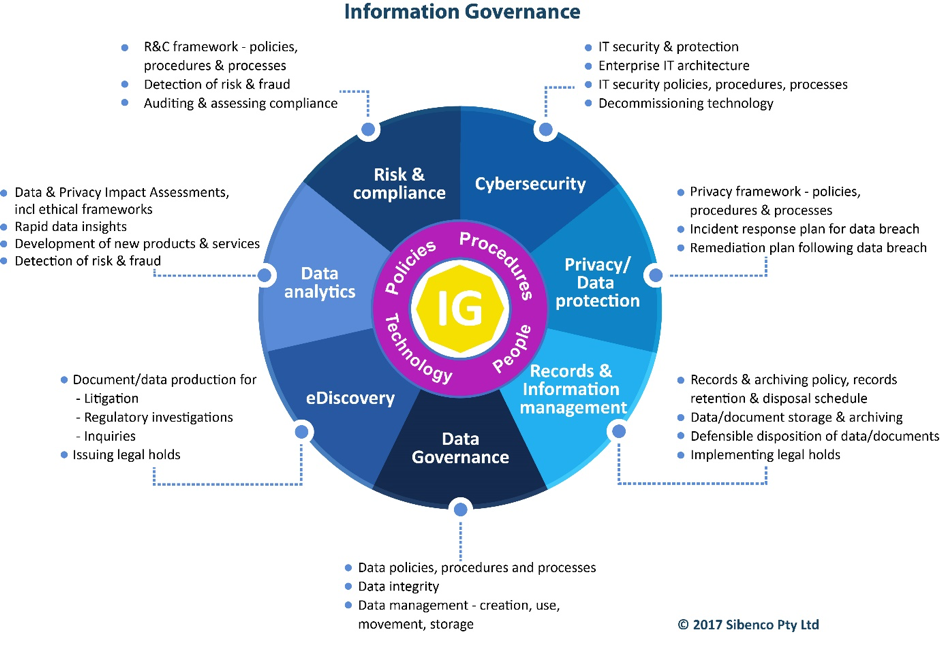

Information governance is the framework, policies, technology and roles for controlling and securing information throughout an organisation to optimise the value of information, meet regulatory and legal obligations, manage risk and support business objectives.[6]

The goal of effective information governance is to maximise the value of information, recognising the potential value of data as the ‘new oil’ and to minimise the risks and costs of holding information. The risks and costs include: those resulting from data breach, eDiscovery (the production of documents in litigation and in regulatory inquiries), ROT – the storing of redundant, outdated and trivial data that increases data storage costs, the costs of eDiscovery, and the costs of additional internal resources to manage data.

Drivers of IG: Litigation, inquiries and royal commissions

The growth of information governance in the United States over the past decade was driven largely by the enormous costs of eDiscovery and document production in litigation and regulatory investigations. The Hayne royal commission provides a current Australian example of the substantial resources and costs involved in document production. The Hayne royal commission which was established in December 2017, has now issued over fourteen hundred Notices to Produce to institutions, requiring them to produce documents within tight deadlines. The notices have required production of documents in some instances covering a 10-year period. The Australian Financial Reviewreported on 28 September 2018, that CBA had responded to 106 Notices to Produce to 30 June 2018.

The Hayne royal commission and large litigation matters involving significant and ongoing document production or large eDiscovery result in teams of people, including lawyers and internal resources, to assist in identifying, reviewing and producing documents, the extensive use of specialised eDiscovery technology, and substantial costs in the millions, and even tens of millions, of dollars. These costs are minimised when there is good information governance, because ROT is disposed of and there is ongoing defensible disposition of data in accordance with records and information record retention policies. This enables relevant documents to be more easily and cheaply identified and retrieved from the vast volumes of data being stored by organisations.

Drivers of IG: Growth in privacy laws and data breach

The emerging driver of good information governance globally is compliance with regulatory obligations, particularly with the growth in global privacy laws. Good data governance and privacy compliance starts with knowing where your data is and mapping it, so appropriate steps can then be taken to secure and control it – for most organisations this is a significant challenge.

The GDPR includes expanded accountability and governance requirements including record keeping, privacy by design and privacy by default, and a requirement for data protection impact assessments to be carried out where high risk data processing is being undertaken. Australian Privacy Principle (APP) 1.2 requires that organisationsmust take reasonable steps to implement practices, procedures and systems that will ensure it complies with the APPs. The Australian Government Agencies Privacy Code issued in July 2018 sets out requirements of APP 1.2 for privacy management and governance, including that agencies are required to carry out privacy impact assessments in relation to all high privacy risk projects.

Boards and senior executives need to be aware that under the GDPR and APP11.2, organisations are not permitted to retain personal information for longer than the lawful purpose for which the data was collected. It means that organisations must either destroy or de-identify data. The touting of data analytics and data as the ‘new oil’ means that many organisations are storing vast quantities of data, including data of customers and employees both past and present. The protection of personal information under privacy regulations requires organisations to understand and properly govern the personal information they hold, including disposing of personal information.

Drivers of IG: Requirement for government agencie

Australia’s Digital Continuity 2020 Policy, sets out as its first principle that information is valued. It requires agencies by 2020 to manage their information as an asset, ensuring that it is created, stored and managed for as long as it is required, taking into account business requirements and other needs and risks. This recognises that information is a key strategic asset and economic resource, and that digital information management enables efficiencies in service delivery, increases opportunities for information sharing and can improve business decisions and accountability. As part of the first principle, agencies are required to implement an information governance framework and annual survey reporting on information governance.

Top-down leadership

Effective information governance requires top-down leadership from the Board to set the strategic objectives and priorities for managing information assets. The objectives will vary according to the nature of the industry, size of the organisation, and where a particular organisation sits in relation to cybersecurity threats, the types of data collected and opportunities to extract value from data, and use of new technologies.

Effective information governance enables Boards and senior executives to be proactive in respect of the opportunities that can be derived from data and technology, and proactive in respect to potential threats. Preventing misuse or data breach of customer personal information is key in industries such as banking and health. For organisations in these industries that collect and store vast quantities of customer personal data there are increasing regulatory requirements, including the need to be able to quickly respond to data breaches of personal information both to comply with the requirements of the NDB Scheme as well as to manage reputation in the public domain and retain the trust of customers.

For other industries, such as mining and pharmaceutical, the primary concern may be to protect valuable intellectual property from cyberattack and theft. Where intellectual property theft is a key concern, then in addition to cybersecurity investments to protect the IT network perimeter of the organisation there will need to be increased information security within the organisation to prevent rogue employees from accessing and/or misusing information. Information security measures will include stricter control of ‘shadow IT’ such as employees using their own devices or apps, through appropriate BYOD policies and IT auditing and surveillance, and human resource risk management. The broad range of issues necessitate a coherent and strategic plan across organisational silos to minimise risks and costs.

A robust information governance framework that is led from the top-down and effectively implemented throughout an organisation will enable this. The Information Governance ANZ Survey 2017 found that 98% of respondents said that defining and implementing an IG framework for their organisation was important, and that should they have the budget and authority to do so, half of all respondents said they would do so as a priority.

Information governance framework

The first step to building an information governance framework is to clearly understand where information is being managed throughout the organisation and the positions of those across the silos responsible for managing the information and/or technology systems. The next step is building an information governance framework and system to facilitate the effective interaction between the stakeholders to ensure the policies and activities undertaken for each of the information areas are aligned with each other, the overarching information governance policy and with the overall strategic goals of the organisations.

The framework includes the overarching information governance policy which:

- sets out an overarching description of how information is governed including leadership and planning;

- describes the factors and business drivers which determine or influence the creation, management and use of information, including legislation, regulations, compliance, risk, and business needs; and

- documents the organisation’s commitment to information governance and provides senior management endorsement.

The Information Governance ANZ Survey 2017 found that 55% of respondents said their organisation governs IG with a formal framework with policies and procedures.

The information governance framework above demonstrates the various areas within an organisation where information is typically managed, although in some organisations there will be more areas. It is the co-ordinating of these areas to efficiently and coherently safeguard that the organisation will deliver on its information governance objectives and support overall achievement of organisational objectives.

Information governance committee

In large organisations, an information governance steering committee is the best mechanism to ensure that the overarching information governance objectives are implemented in a consistent and systematic way. It may take different forms, to suit the needs and structure of the organisation including: board, committee, working group, or as part of an existing governance committee.

It is important that the committee comprise all key information stakeholders to encourage collaboration and effectiveness of information governance activities. The committee members may include – General Counsel (GC), Chief Information Security Officer (CISO), Chief Privacy Officer (CPO), Chief Data Officer (CDO), Chief Marketing Officer (CMO), Chief Data Scientist (CDS), Records & Information Manager (RIM) and others appropriate to the needs and priorities of the organisation.

The information governance steering committee should have a suitable Chair to ensure the committee:

– is collaborative to ensure that those members of the committee lead their respective areas to break down information silos with a culture of information and data collaboration;

– is well-structured, meets regularly, and has a clear agenda that is implemented and achieved.

Senior executive responsible for information governance

Best practice information governance includes the appointment of a dedicated senior executive responsible for leading information governance and accountable for enterprise wide information governance. This may be the included in the responsibilities of an existing senior executive, but best practice is the creation of a dedicated position – the Chief Information Governance Officer (CIGO). The Information Governance Initiative (IGI), a US IG think-tank describes the CIGO’s role as ‘to balance the stakeholder interests from each facet of IG and develop the right operational model for the organization.’

As part of the Digital Continuity 2020 Policy, the creation of the CIGO role for Australian government agencies‘is critical for digital innovation and capability, and for championing the importance of effective information management’. The CIGO role is also important for establishing and maintaining a culture for a more accountable and business-focused information management environment.

Information governance reporting

There should be regular information governance reporting of progress on initiatives, programs as well as evaluation and auditing. The reporting should be to the designated C-level executive responsible for information governance, such as the CIGO and/or the information governance steering committee.

The senior executive responsible for information governance, such as the CIGO, and/or the information governance steering committee then report to the relevant Board committee. The relevant board committee may be the audit and risk committee or another relevant board committee. It is critical that there is at least or more one member of the committee (and on the Board) that understand the requirements of good information governance, including privacy regulatory obligations, the role of technology and cybersecurity.

Conclusion

The growth of data breaches and privacy regulatory requirements, together with the costs and burden on institutions involved in responding to the current Hayne royal commission, should be prompting boards to review and assess whether their current information governance is adequate to manage information risks and meet legal and business requirements.

Good corporate governance requires a robust information governance framework. This will include an information governance steering committee and/or dedicated senior level executive with the responsibility and accountability for information governance. Importantly, information governance reporting needs to feed into relevant Board committees, so that the board has appropriate oversight.

Effective information governance requires top-down board and senior executive leadership to enable the organisation to deliver continual strategic and proactive governance as digital disruption impacts the organisation and digital transformation continues.

With good leadership, a properly executed information governance framework and program should deliver effective security and control of data and information by minimising risks and reducing costs of holding information and maximising the value of information held by the organisation.

Professor Michael A Adams FGIA(Life) FCIS, Professor of Corporate Law & Governance, School of Law, Western Sydney University and

Susan Bennett, FGIA, CIPP/E, Principal, Sibenco Legal & Advisory, Co-founder and Director of Information Governance ANZ

This article was published in Governance Directions, November 2018, Vol 70, Issue 10

[1]https://financialservices.royalcommission.gov.au/Pages/interim-report.aspx

[2]Adams, M. (2018) “Three Pillars of Corporate Governance” 70(6) Governance Directions, p 302.

[3]http://www.infogovanz.com/featured-articles#iganzsurveyreport-anchor

[4]Adams, M. (2018) “Top 2018 governance concerns: #SEMTEX” 70(8) Governance Directions,p 477.

[5]Adams, M. (2012) ‘Global Trends in Corporate Governance’ 64(9) Keeping Good Companies516, 518.

[6] See also – What is Information Governance and how does it differ from Data Governance?– Governance Directions, September 2017, Vol 69, Issue 8